Five Hours of Jazz

I came home from work one day to find a smaller-than-average man sitting on my couch. My son had closed the door to his room and the television was playing at full volume. I could see the black frame of the man's thick glasses. I could see his thin white hair. I just had no idea who he was.

"Who are you?" I asked.

"There are pharmaceuticals in the water," said a plumber on television.

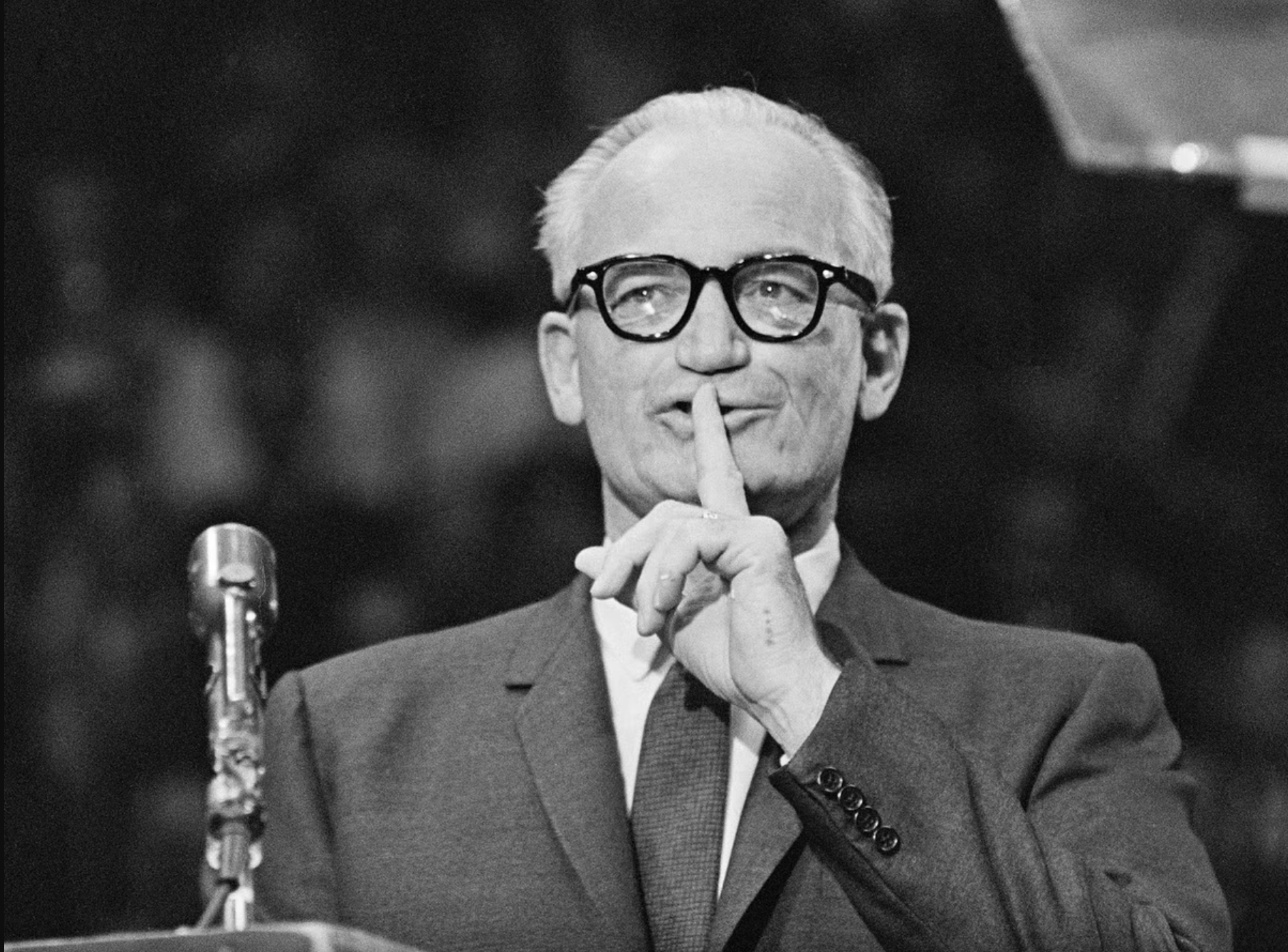

I walked around to the front of the couch and recognized the man: he was a politician. Or, rather, a slightly-smaller-than-average 3D-printed copy of a politician, who was dead now. Barry Goldwater was his name, the senator. This one was made of white plastic and his smoking jacket was cuffed perfectly. On the left side of his hand was a conspicuous tattoo: four black dots and a closed parenthesis.

I sat beside him and watched TV for a little while, hoping my son would come out of his room. He'd laugh, I thought, seeing us sitting there like that, wrapped up in a European detective show. He needed a laugh. Once the vicar had mimicked birdsong to solve a mystery, I got up to chop the escarole.

At the dinner table, I asked my son about Barry Goldwater’s tattoo.

"Just Google it," said Man. He had chosen the name Man himself.

"I did Google it," I said. "Google said he was head honcho in the Smoki."

"If you use their language I'm going to throw up on you," he said. "You do know the Smoki were a group of wealthy white men who met every year at a fairground in Prescott to wear red-face and appropriate Hopi rituals. The only reason they got away with it was because Arizona was a new state with no history or culture on which to ground itself except for a flimsy Wild West mythos that flattens real people into ideas."

"Did you learn this in school?" I asked.

"Leave me alone," said Man.

"Civics?" I asked.

"Father," he said, and I salted the lettuce. My son never called me father. I think I liked it, the power built into the formality, I just wasn't sure whether all this was a confused grief at work. Man had taken the sudden death of his mother in ways that were entirely mysterious to me. When he was little, my son would ask all sorts of questions. At the urinal he'd ask me about the bright blue absorbent cake. He'd ask about the ingredients in Tylenol and how to treat osteoperosis. I knew these things because I am a doctor. But there’s no real way to answer a question that hasn’t been asked.

My son stood Barry Goldwater up from the couch and walked him over to the table. They both looked so serious. Man sat the senator down across from me and rested his plastic hands beside a decorative gourd. I noticed the tattoo again, shining in the light.

"You rafted the Grand Canyon," I said to Goldwater. I figured some real respect might win my son over. The senator’s eyes were painted a deep sky blue.

“You know he can’t hear you,” said Man. "It's a painted mold."

"He or it?" I asked. "I think the distinction matters."

"Father."

"You know he had thousands of Kachina dolls," I said. "I have a book of his photographs, actually. Barren landscapes, indigenous portraits. He loved to fly planes."

Man got up. "I'm leaving the table now," he said.

On television, a Scandinavian detective was waiting for a killer in the fjord, his pistol hidden under the water. He was just so slim. Did Goldwater have genitals? He was otherwise anatomically accurate, I thought, and rinsed a plate. I was about to dump the remaining escarole into the disposal when I saw Goldwater sitting alone at the table.

Of course he couldn't eat. But I knew he wanted something. I went into the office and found a dusty Kachina Doll. My wife had purchased it five years ago at a craft fair in Prescott. The doll's face was painted a light blue, a little like the senator's eyes. I dusted it off and moved it to the center of the table. I set it right in his line of vision. When I did this, I felt better.

From the lounge in the hospital the next day, I emailed the two Jesuit brothers who taught Man's 3D printing class. I'm a doctor, I wrote, and I might be able to help the class better understand the many practical applications of 3D printing in the medical field. The reply was almost immediate and unsigned.

“The father of Man,” it read, “is always welcome in our class.”

We arranged for a time to meet later that afternoon. When I arrived, the two robed Jesuits greeted me at the science building’s grand archway with a hug. Inside the auditorium, all the students were seated and quiet. I half-waved at my son, being careful to exercise the right amount of discretion, and one of the Jesuits smiled at my enthusiasm, showing his jagged yellow teeth. He touched my back and ushered me to the first row. The room was lit with bright fluorescents. Hundreds of boys filled up the stadium seating. Barry Goldwater stood at the front of the room gripping the rostrum with his tattooed hand. He, still made of plastic as far as I could tell, wore a clean black suit today.

The Jesuit with bad teeth began a guided meditation.

"Forget history," he said. "Today it's only you and Barry Goldwater, the senator, alone in a Safe Place of your choosing. You're perched on a moss-covered rock. Or you're together in the Sea of Tranquility. Yes, with Barry Goldwater you can travel even to the moon. Now he leans over to whisper—listen. What does he say?”

And so on and so forth, a bunch of mystical nonsense that made for an absolutely incoherent way to introduce a five-term senator to the boys, I thought. Better to mention the import of Goldwater’s failed ’64 presidential run, how the loss put Raegan in office. Or at least get into how as a stubborn old man he used his celebrity to fly a reconnaissance mission alone through Vietnam; how he built motorcycles, outfit his home toilet with a humorous intercom, and set up a ham radio at the North Pole. I had done all the research. But apparently none of it mattered.

After the meditation, students had the chance to respond. One of the boys said he had a wrestling match soon. He wanted either to gain or lose weight, but couldn't decide which. The senator had told him to plant a tree.

I waited for Man to speak, but he kept quiet. If I weren't here, I knew he'd talk. He'd get into the senseless pain life had brought. He’d say how all the pieces once fit together and now he owned a 3D-printed senator.

When the students were done, the Jesuits invited me up to speak. Goldwater stayed at the podium. I wasn't just about to move him. I stood to his side and talked about the obscure theoretical applications of 3D-printed ovaries for a little over an hour.

"We have to consider all sides of artificial insemination," I said. But no one was paying attention to me. I wasn't paying attention to me. We were all focused on the senator. The look on his face was one I can only call commanding. The tattoo on his hand looked so dark now, almost wet with meaning. I had the sudden urge to suck out the ink. What is it, I said. Tell me what you have to say, because I’m listening. His teeth were parted, just so.

"That was very embarrassing for me," my son told me later that afternoon. We had driven home together after class and set up Goldwater on the couch. "I want to reiterate that he doesn't speak. It's a lot like a statue. Try not to overthink it."

"Then you do consider him human," I said, pointing my finger.

"Stop," he said. "I don't know."

I followed him into his room and he put on headphones, sat in a tall leather chair, and began to play a Tombstone-themed battle royale game, choosing to play as Doc Holliday, the tubercular dentist. I paced around behind him while he played. I picked up a green Burberry shirt from the floor, folded it, and then dropped it again. I was unsure whether to do his laundry. His mother had done his laundry every day until a few hours before she died. Most of the clothes in the room hadn't moved since.

After a few minutes, Man left the bedroom and I immediately crawled under the bed. There wasn't a single book hidden there. Nothing about Goldwater. About politics, unions, or the attempt to flood the Grand Canyon. There was nothing about Robert Kennedy or the John Birch Society. I hit my head on the bed-frame when I heard him shout.

"Where is he?" Man was panicked. By the time I was back in the sunken family room, I understood. Goldwater was missing. My son had torn all the pillows off the couch. The blood vessels around his eyes had burst and he beat his thigh with a fist, growing younger by the second.

He was crying on the floor and this was no time for thought, I thought, and stroked the trim beard on my face. On television a man riding a horse advertised a shotgun. The desert spread out behind him like an empty promise. I knew I could make things right.

I picked up my son and with some difficulty set him on the couch. I kissed his forehead. “I am your father," I said. "And I’m going to fix this.”

I checked the alarm console. On the CCTV we had installed to watch coyotes carry off rabbits and small dogs I scanned backward until I saw them. It had been only ten minutes ago: the two Jesuits carrying Barry Goldwater like firemen down the driveway. I paused, squinted, and saw the tattoo on both of their hands. That was the answer, I knew. I just didn't know the question. I took out a black sharpie from the drawer and marked my own hand: four dots and a closed parenthesis. I started the car.

The low beige buildings of my son's highschool were spread out from one another on the big open campus. I walked between the shaded rows of old metal lockers, finding the hundred-degree heat of the evening almost pleasant. I knocked on a side entrance of the small wooden church. A hunched man opened the door.

"I'm looking for some Jesuits," I said.

He laughed and nodded into his chest.

“Sure,” he replied. “There aren’t many more of us left.”

He gestured for me to follow down a carpeted hall. We entered a dim room with red couches and velvet curtains. Hot candle wax dripped on the low wooden tables. I looked behind one of the curtains, just acting on a hunch. The old Jesuit giggled back like a child, watching me search.

"Do make yourself at home," he said.

I opened books at random and looked under cups. There were portraits on the wall: Ignatius of Loyola, John McCain, Miguel de Cervantes. Next to a painting of St. George was a photograph of Barry Goldwater holding a cigarette in the shadows. A self-portrait, I later learned. He resembled a Jewish cowboy, stubble on his face. A little like me, I thought. Maybe it was that simple.

I turned around and saw the two Jesuits standing on the carpet.

The one with bad teeth was eating little gummy candies.

"You took my son's senator," I said.

“Yes," said the one without candy. "And we can explain. Just let me make us some tea first. Black?" he asked.

"Milk," I said, and the other one offered me a cactus candy.

I shook my head and asked what the hell was going on.

"My son has never been interested in the politics of Arizona," I said.

We sat down on the couch and he replied, "I'm afraid it's not a matter of politics. A man can become an idea, and an idea is a powerful, little worm of a thing. He's a very handsome guy, Mr. Goldwater.”

“Are you saying this is homoerotic?” I asked.

“For us, most things are. Haven't you been to a rock concert and heard the audience screaming? That’s politics for you—or it’s God. All that pining. The desperate dreams and quiet hopes. We Jesuits know it well. You could even say it’s our stock and trade, this yearning. Divine love.”

The other one came back with tea and simple sugar cookies. He handed me the plate and I threw it to the ground like a sulky toddler. Nothing shattered, but the milky assam seeped through the wooden floorboards. I knew someone would have to clean it later, probably the old man, but choices have to be made when the family is at stake. I held my hand out in a fist.

"Don't be upset," said the Jesuit, and handed me a rag.

"What I want is to join the Smoki," I said.

"The what?" said the Jesuit eating candy.

"Oh,” said the other, gently unclenching my fist. “Goldwater had this same tattoo. You want to come along tonight?”

His own hand had no marks, I noticed. Only spots from the sun. I was getting worked up. “You know it was illegal for the Hopi to perform their own religious rituals until 1973? Goldwater did a snake dance every year at that fairground.” I said. "And the pipe bombs in Tuba City—what do you think about those?”

"Please," the Jesuit was rubbing my back now and I have to admit it felt good. A little maternal. "You're lost," he said. "Which is okay, it’s easy to misunderstand one another. We took the senator for a meditation tonight. We hold them for all types of people. We have one in Prescott later this evening, for a special team at Google. Our methods aren't orthodox, of course, but no one’s perfect. And you are here now, aren't you? Why don’t you come along with us?”

“I'll come,” I said. "In my own car."

They got in a white van, and I drove behind them. On the highway north out of town I called a student I knew from my wife's spin class. “I'll give you three thousand dollars to babysit my son,” I said. She agreed. I called Man and told him they were holding an emergency pharmaceutical conference. I told the hospital I was ill and shut off my phone.

The van drove north on the I-17. We passed the city of Anthem and a forest of dead yellow trees. Scrub sloped up the mountains all around us. On the NPR syndicate Click and Clack were signing off. A voice announced that up next was five hours of jazz.

Outside Prescott, we came to a gigantic dirt lot at the foot of a hiking trail. More than a hundred cars were parked there. All of them had California license plates. The two Jesuits got out of their van, carrying Goldwater, motioning for me to follow. They lit the trail with a headlamp and we walked down steps that had been carved from the rockface. I heard a snake rattle, or at least thought I did.

The retreat structure was set inside a mountain, a little like the lair of a James Bond villain. The pneumatic doors opened to a massive room identical to the auditorium at my son's school. There were the same fluorescent lights, the same stadium seating. Hundreds of men sat in silence, wearing similar down jackets, their heads turned to Goldwater in reverence. The senator stood at the front of the room—wearing Levi's and a suede jacket now—silent.

A Jesuit made the sign of the cross.

"Let us pray," he said.

They began a silent meditation and I stood from my seat. Everyone's eyes were closed but His. They had all focused inward on their respective spiritual planes and no one noticed me pick up the senator and hoist him over my shoulder. To my surprise, he was light, but awkward to carry. I used Goldwater’s heel to open the exit and his cowboy boot went slightly askew.

Outside I walked back up the stone steps at a clip. I was afraid but no one followed us. I sat the senator down in the passenger seat of the car, surprised at how pliable his joints were. It was like a healthy young patient at the hospital. I tried to pull off his clothes, but the jacket was too stiff.

In the rearview mirror I saw our faces, lit red from the dash. Goldwater's own was grim, focused on the road ahead. Mine wouldn't stop moving. He had done nothing to me and it didn’t matter now.

On the outskirts of Prescott, I found a gun store called Bear Arms. The cashier inside suggested an automatic rifle. I said no. I just needed one shot.

“Guard the home?” he asked.

“Something like that.”

Gun in the trunk, I drove until we got to deserted territory, off road, where I could feel the Mercedes jolt over rocks too big for its suspension. A cactus dented the front bumper, but I kept driving. I can buy a new car anytime I want. I parked and waited for the sun to come up.

In the red morning light, I took the senator out and stood him up beside a spruce. A pygmy nuthatch sang in the distance. The air was fresh, clean. I had never fired a gun and I was afraid of the recoil. I walked up to Barry Goldwater for the last time and touched him with my index finger. His skin was so soft. "Who are you?" I asked, and knocked twice on his temple. The sound was hollow and dull.

I walked twenty paces. A pinecone crunched under my foot. I aimed and shot the gun. The senator bounced off the needles of the tree and fell down. The buckshot had shredded his jacket. I approached and shot him again, until the face was unrecognizable and all the paint had splintered off. He became nothing but its base materials. Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene, Polylactic Acid, and who knew what else.

I found a motel and slept. I locked the door and ate salted cashews in the bathtub. I wanted to collect my thoughts. I wanted to be on my own for a very long time.

On Sunday, an hour before I got to Phoenix, I called the babysitter and said she could head out. I'd be there soon. She gave me the payment info and said not to worry. Everything had gone according to plan.

I parked in the garage when I got home, shotgun still on the passenger seat. Already I felt closer to my son, to Man. I had helped him and he would never know the details. He didn't need to know. Now it was I who had questions and no clue how to ask them. Maybe now I'd buy my own 3D printer or take up a new hobby. Or I’d do nothing. Too much in this life isn't put here for us to understand, I understood, and walked inside. Man had shut the door to his room. Barry Goldwater was sitting on the couch, in front of the television. I turned it on and sat next to him, holding his smooth, unmarked hand, feeling for warmth: the two of us there, peaceful and perfectly still, for just a moment, while a commercial for a fast electric truck played on at full volume.